Burle Marx: el artista que supo pintar con plantas

Brasil está repleto de toda clase de plantas, flores y árboles exóticos. Pero hasta la irrupción del paisajista brasileño Roberto Burle Marx, sus compatriotas menospreciaban en gran medida las riquezas naturales que florecían en torno a sus casas. Ahora, el gigante sudamericano, con una retrospectiva en el museo Paço Imperial de Río de Janeiro, honra a un visionario que veía arte en los paisajes.

Por: Larry Rohter. Para The New York Times y Clarín

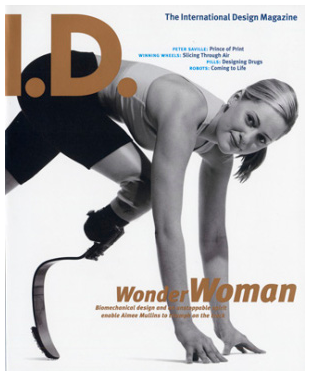

COPACABANA. La estética de la playa más famosa de Río, fruto de la planificación de Marx.

«Burle Marx ha inventado el paisajismo tropical tal como lo conocemos hoy en día pero, al hacerlo, también ha hecho algo más importante», puntualiza Lauro Cavalcanti, director de una exposición dedicada a la obra de Burle Marx que se exhibirá en marzo en el museo Paço Imperial, aquí en Río.

«Al organizar las plantas nativas según los principios estéticos de la vanguardia artística, especialmente el cubismo y el arte abstracto, ha creado una nueva gramática moderna para el diseño de paisajes internacional».

Burle Marx nació en 1909 y, para celebrar su centenario, el museo se ha propuesto mostrar todo el alcance de su creatividad (la muestra viajará después a San Pablo). Además de presentar modelos a escala y dibujos de sus proyectos de diseño paisajístico más célebres, la exposición incluye cerca de 100 cuadros suyos, así como dibujos, esculturas, tapices, joyas y decorados y trajes que diseñó para producciones teatrales.

«Era un hombre verdaderamente erudito y polifacético», comenta William Howard Adams, el comisario jefe de una exposición sobre Burle Marx que se presentó en el Museo de Arte Moderno en 1991. «Pero lo que llama más la atención en él es que veía el diseño paisajístico como una disciplina de igual relevancia que la arquitectura, no como un telón de fondo o una decoración». Burle Marx siempre se vio a sí mismo, ante todo, como un pintor. El diseño paisajístico, escribía en cierta ocasión, «no es más que el método que he encontrado para organizar y componer mis dibujos y pinturas, utilizando unos materiales menos convencionales».

Fue mientras estudiaba pintura en Alemania durante la República de Weimar cuando Burle Marx, como él mismo contaría más tarde, se dio cuenta de que la vegetación que los brasileños desdeñaban por considerarla matojos y malas hierbas, prefiriendo en cambio pinos y gladiolos importados para sus jardines, era extraordinaria. Mientras visitaba el Jardín Botánico de Berlín, se sorprendió al encontrar muchas plantas brasileñas en su colección, y rápidamente se fijó en las posibilidades artísticas sin explotar que tenían sus variados tamaños, formas y colores.

Burle Marx tenía ascendencia alemana por parte de padre y francesa por la de su madre. Nació en San Pablo, aunque siendo muy joven se trasladó a Río de Janeiro, donde tuvo como vecino al arquitecto modernista Lucio Costa, el futuro diseñador de Brasilia, quien le hizo a Burle Marx sus primeros encargos. Burle Marx es especialmente conocido por sus muchos proyectos ambiciosos aquí en Río.

«El rostro de esta ciudad lleva su huella», comenta Cavalcanti. El parque Aterro do Flamengo, el más grande de Río y que se ubica junto a la bahía, construido sobre un paseo marítimo ganado al mar, es un ejemplo inicial de uno de los proyectos más característicos de Burle Marx. Pero, en lo que a líneas de costas escarpadas se refiere, no hay nada que supere los paseos de Copacabana, con sus coloridos mosaicos abstractos de piedra que se extienden ininterrumpidamente en toda la longitud de la playa. Partiendo de los pisos superiores de los edificios que bordean la Avenida Atlántica, Burle Marx parece haber pintado un único lienzo de casi cinco kilómetros de largo. «Aunque le gustaba diseñar jardines para sus amigos, lo que más le satisfacía era trabajar en espacios públicos», señala Haruyoshi Ono, un arquitecto paisajista brasileño que empezó a trabajar con él en 1965 y actualmente dirige la empresa de diseño paisajístico que Burle Marx fundó en los años cincuenta. «Solía decir que cuanto más grande y abierto era un proyecto, más le gustaba, porque podía disfrutarlo gente de todas las clases sociales».

Durante la década pasada, Burle Marx se ha convertido en «una especie de héroe» para una nueva generación de arquitectos paisajistas estadounidenses, según explica Karen Van Lengen, decana de la Escuela de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Virginia. Dice que se le admira no sólo por sus formidables habilidades técnicas como artista, sino también por centrarse en los aspectos científicos del paisajismo y por la atención que prestaba a las comunidades vegetales y a su relación con el medio ambiente.

Burle Marx tenía casi tanto de botánico como de arquitecto paisajista, por más que fuese autodidacta. Hay más de 50 especies vegetales que llevan su nombre.

«Burle Marx fue profético en su respeto por las plantas y su capacidad para organizar el conjunto, en su habilidad para ver el jardín como un experimento estético a la vez que una parte del ecosistema», dice Van Lengen. «Ése es el reto de los arquitectos paisajistas actuales: reunir esas energías».

A New Look at the Multitalented Man Who Made Tropical Landscaping an Art

By LARRY ROHTER

RIO DE JANEIRO — Brazil teems with jungles, forests and all sorts of exotic plants, flowers and trees. But until the Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx came along to tame and shape his country’s exuberant flora, his countrymen had mostly disdained the natural riches that, often literally, flourished in their own backyards.

“Burle Marx created tropical landscaping as we know it today, but in doing so he also did something even greater,” said Lauro Cavalcanti, the curator of an exhibition devoted to the work of Burle Marx that runs through March at the Paço Imperial museum here. “By organizing native plants in accordance with the aesthetic principles of the artistic vanguard, especially Cubism and abstractionism, he created a new and modern grammar for international landscape design.”

Burle Marx was born in 1909, and to mark that centenary the museum set out to show the full extent of his creativity. (The show travels next to São Paulo.) In addition to scale models and drawings of his most celebrated landscape design projects, the exhibition includes nearly 100 of his paintings, as well as drawings, sculptures, tapestries, jewelry, and sets and costumes he designed for theatrical productions. The goal is to show how his work in one field bled into his work in the others.

“He was truly a polymath,” said William Howard Adams, the chief curator of a Burle Marx exhibition presented at the Museum of Modern Art in 1991. “But the thing about him that really stands out is that he regarded landscape design as an equal partner with architecture, not as a backdrop or decoration, and elevated it to that level.”

For his part, Burle Marx always thought of himself first and foremost as a painter, which explains the abundance of canvases in the show. Landscape design, he once wrote, “was merely the method I found to organize and compose my drawing and painting, using less conventional materials.”

It was while studying painting in Germany during the Weimar Republic, as he would later tell it, that Burle Marx realized that the vegetation Brazilians then dismissed as scrub and brush, preferring imported pine trees and gladioli for their gardens, was truly extraordinary. Visiting the Botanical Garden in Berlin, he was startled to find many Brazilian plants in the collection and quickly came to see the untapped artistic potential in their varied shapes, sizes and hues.

“The way he synthesized art and horticulture in three-dimensional design is really quite exceptional,” said Mirka Benes, a landscape historian who teaches at the University of Texas at Austin. “He truly had a painter’s eye, which you could sense in his superb sense of color and form, and he had an understanding of the tenets of Modernism and Dada, having clearly known and studied the work of people like Hans Arp.”

Like Arp, Burle Marx was of German descent on his father’s side and French on his mother’s side. He was born in São Paulo, but moved at a young age to Rio de Janeiro, where one of his neighbors was the Modernist architect Lucio Costa, the future designer of Brasília, who gave Burle Marx his first commissions.

Although Burle Marx had a hand in designing some parts of Brasília, including its hanging gardens, he is especially known among Brazilians for his many ambitious projects here in Rio. “The face of this city bears his imprint,” Mr. Cavalcanti said.

Rio’s largest park, the bayside Aterro do Flamengo, built on reclaimed seafront just southwest of downtown, is an early example of one of Burle Marx’s signature projects. But for sheer sweep, nothing surpasses the sidewalks of Copacabana, with colorful abstract stone mosaics extending unbroken the entire length of that beach. From the upper floors of the buildings that line Avenida Atlantica, Burle Marx appears to have painted a single canvas about three miles long.

“While he enjoyed designing gardens for friends, what gave him the most satisfaction was to work with public spaces,” said Haruyoshi Ono, a Brazilian landscape architect who began working with him in 1965 and today directs the landscaping company that Burle Marx founded in the 1950s. “He used to say the larger and more open a project, the more he liked it, because it could be enjoyed by all social strata.”

Burle Marx’s most elaborate and time-consuming effort, however, may have been an abandoned estate he bought on the outskirts of the city in 1948 and turned into a home, studio and garden complex. Now a national landmark and tourist attraction with more than 3,500 species of plants, it functioned as his workshop, laboratory and office until his death in 1994.

At the peak of his career, Burle Marx was highly esteemed among his peers in the United States. In 1965 the American Institute of Architects awarded him its fine-arts prize, saying that he was “the real creator of the modern garden.”

But unless they traveled to the tropics, American gardeners had little opportunity for direct exposure to his work. Although he designed some gardens in temperate climates, notably for United Nations buildings in France and Austria, “you certainly can’t have a Burle Marx garden in Wisconsin or Vancouver,” Ms. Benes said, “unless you translate his ideas to local plant systems, which looks easy on paper but is not.”

In the United States, Burle Marx’s earliest known project was the Burton Tremaine house in Santa Barbara, Calif., commissioned in 1948. He also designed gardens for the Hilton Hotel in San Juan, P.R., and the Organization of American States headquarters in Washington, and was hired to revamp Biscayne Boulevard in Miami.

Over the last decade he has emerged as “something of a hero” to a new generation of American landscape architects, said Karen Van Lengen, dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Virginia. He is admired not just for his formidable technical skills as an artist, she said, but also for his focus on the scientific side of landscaping and the attention he paid to plant communities and their relationship to the environment.

Burle Marx was almost as much a botanist as a landscape architect, although largely self-taught. More than 50 plant species have been named for him, and he was one of the world’s leading experts on bromeliads, the plant family to which the pineapple belongs. Even in old age he regularly traveled to the Amazon and Southeast Asia to search for unusual and attractive plants that he could cultivate in his home garden and then use in new projects.

“Burle Marx was prescient in his reverence for plants and his stewardship of the whole nursery, for his ability to see the garden both as an aesthetic experiment and also as part of the ecology,” Ms. Van Lengen said. “That’s the challenge for today’s landscape architects, to bring those energies together.

“Burle Marx was already doing that before most people were even thinking about it, so he really stands alone.”

–

By JAMES BROOKE,

Published: June 6, 1994

Roberto Burle Marx, whose mark on Brazil’s landscape ranged from the undulating mosaic sidewalks of Copacabana Beach to the hanging gardens in the new capital of Brasilia, died on Saturday. He was 84 and lived in his lush, botanical retreat, a former coffee farm, 35 miles from here.

He died of congestive heart failure, friends said.

During a 60-year career, Brazil’s most prominent landscape artist brought his nation’s rich flora out from Europe’s shadow and became a tireless champion of Brazil’s orchids, palms, water lilies and bromeliads.

His nearly 3,000 landscape projects in 20 nations ranged from the gardens of the Organization of American States headquarters in Washington to a redesign of Biscayne Boulevard in Miami, from the gardens of the Unesco headquarters in Paris to a tropical garden under glass at Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania. Designed a Rio Park

In Brazil, he was best known for Rio’s postcard Flamengo Park — 300 acres of lawns, playing fields, artificial beach and automobile parkway that connect the city’s financial center with beachfront residential neighborhoods.

«Unlike any other art form, a garden is designed for the future, and for future generations,» Mr. Burle Marx said in an interview prior to his 1991 show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibit, «Roberto Burle Marx: The Unnatural Art of the Garden,» was the museum’s first devoted to a landscape architect.

Born in Sao Paulo in 1909 to a Brazilian mother and a German father, Mr. Burle Marx only discovered the power and variety of Brazilian plants when he traveled to Berlin in 1928 to study at the Dahlem Botanical Gardens. Moving to Rio on his return to Brazil, he was experimenting in his backyard with local flora when he caught the eye of a neighbor, Lucio Costa.

Decades later, the two worked together on the daring design for Brasilia, the new capital in the central high plains. Mr. Costa designed Le Corbusier-style buildings and Mr. Burle Marx designed landscapes, which ranged from monumental parks to the hanging gardens of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

«He was the creator of Brazilian gardens,» Mr. Costa said on Saturday. «He was an innovator because he associated abstract art with landscaping. Before him, our gardens were planned following French and English models.»

A self-taught botanist, this bear of a man with an unruly shock of white hair came to have 13 plant species named after him. Mr. Burle Marx also became a pioneering critic of Brazil’s treatment of its historic and biological heritage.

Although he escaped a kidnap attempt last year, apparently in an effort to get ransom, he criticized Rio’s steady retreat behind walls, saying that a move last year to enclose city parks behind cast iron fences amounted to «Rio in a cage.» On one occasion, he stalked out of a Brazilian Embassy in Greece when he encountered, in a waiting room, a plastic plant.

Raising alarms about Amazon destruction decades before it became fashionable to do so, Mr. Burle Marx warned in 1971: «I fear that by the time people become enlightened, there won’t be any more forests in this country.»

–

By LARRY ROHTER

Published: July 29, 2001

EVEN in a city as spectacular as Rio, a time comes when you feel you just have to get away from it all, if only for a few hours. So early one recent Sunday morning my wife, Clotilde, and I got into our car and headed west along the coast from our apartment in Ipanema, past the Sun Belt-inspired suburban sprawl and clutter of the Barra da Tijuca until we reached a tranquil green refuge known as the Sítio Roberto Burle Marx.

Roberto Burle Marx was Brazil’s most celebrated modern landscape designer, often working in tandem with the architect Oscar Niemeyer, and in 1949 he was looking for a secluded place to live and store his growing collection of rare plants. About an hour’s drive from Rio, near a fishing village called Barra de Guaratiba, he found what he was looking for: an abandoned banana plantation with a small country house, a 17th-century chapel and 90 acres of grounds.

Today the Burle Marx museum and home contains one of the most important collections of tropical plants in the world, some 3,500 species that Burle Marx gathered from all over Brazil as well as from places as far away as Indonesia and Hawaii. It is open to the public six days a week, and strolling the estate amid towering palm trees while listening to songbirds and cicadas and observing the rock gardens and waterfalls that Burle Marx created for his own amusement proved to have a wonderfully calming and restorative effect.

Burle Marx also collected paintings, jewelry, glasswork, pottery, wind chimes, shells and Baroque religious images, which he arranged skillfully in his home, which only began receiving visitors in 1999, and in the two large open-air ateliers built to his specifications. »He liked to mix styles,» our guide, Ana Paula Costa, told us dryly, and the objects displayed in and around the house reflect that eclecticism — or promiscuity, if you prefer.

At the rear, for instance, is a series of stone structures and bubbling fountains, recalling both Frank Lloyd Wright and a Japanese monastery, that Burle Marx used for parties, judging by the barbecue that still functions. Even more striking was the second of the studios, a huge, austere structure that was finished only after his death in 1994 at the age of 85. Burle Marx’s own paintings are on view here, as are his library, a tapestry and several sculptures.

It was getting on toward lunch by the time we finished our visit, and we could easily have stopped at any of several nearby excellent fish restaurants.

We already knew Tia Palmira, the most celebrated of the group, with its simple wooden tables on a promonotory overlooking the beach, and had several times enjoyed spicy fish stews there. But we were in a mood for something new, and so drove a few miles farther west to Quatro Sete Meia.

To our delight, we found ourselves in a postcard-fantasy setting of what Brazil should be. Our table, at an open window in what once was a fisherman’s house, overlooked the sea, and in the shallows just a few yards away, white egrets hunted for fish or glided in graceful flight just above the waterline. Behind them, simple fishing boats painted in pastels stood at anchor, framed against a placid azure sea that stretched away to a distant mountain range.

In those surroundings, the meal itself could easily have been eclipsed. But it wasn’t. After a tasty appetizer of fresh sirí, or spiced and breaded crab, we opted for one of the moquecas, or stews, for two that are the specialty of the house. We had our choice of shrimp, fish, squid, octopus or mixed crustaceans, but went with the shrimp, at $15, which was more than enough for the two of us; we accompanied it with a pair of $2 batidas, a favorite Brazilian cocktail that mixes sugar cane liquor with fruit juices like lemon, coconut or pineapple.

After a stop along the road to buy fresh shellfish from the fishermen whose stalls line the highway, our next and final stop, heading back to the city, was the Casa do Pontal, at Estrada do Pontal 3295 in the Recreio dos Bandeirantes neighborhood. Finding the place was a bit of a challenge, since the numbering system is not sequential, the building is set back from the road in a country house with little identification, and parking is somewhat haphazard.

We were immediately disarmed, how ever, once we crossed the threshold and read the idealistic declaration of purpose of this singular museum devoted exclusively to Brazilian naïve and folk art. »In a corrupt world, full of violence and hatred, it is a great comfort to be able to enter a universe created by the skilled hands of humble and honest artists,» the statement proclaims.

Like the Burle Marx museum, the Casa do Pontal is the result of one man’s vision and persistence — in this case a French intellectual named Jacques van de Beuque, who arrived in Brazil in 1946 and began collecting Brazilian popular art. In those days, most educated Brazilians scorned the humble creations of illiterate artisans from the interior of their country, but Mr. van de Beuque knew better, and eventually amassed 5,000 works by more than 200 artists.

The principal charm of the collection lies in the beauty of its portrayal of traditional rural Brazilian life, especially that of the poor, arid Northeast.

Moving from room to room, we encountered eye-catching clay sculptures, wood carvings and cloth and metal tableaus that faithfully depicted religious and music festivals and farm and family routines. The entire cycle of life was portrayed here with a charming guilelessness, from birth and schooldays through courtship and marriage, all the way up to death, burial and mourning.

We were so enchanted by what we saw that we had to be gently ushered out the door at closing time. A few days later a Rio newspaper published an interview with the Portuguese novelist José Saramago, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1999, in which he confessed that he had been so moved by a visit to the museum that it ended up inspiring his latest novel, »The Cavern.»

»Brazil should consider this place a national treasure, more important than . . . Corcovado» — the 125-foot statue of Christ that is the emblem of Rio — Mr. Saramago declared. After a few hours spent contemplating the works of gifted but obscure artists with names like Zé Caboclo, or Joe Hillbilly, we found it hard to disagree.

Exotic plants, exotic food

Museums

To visit the Sítio Roberto Burle Marx, Estrada da Barra de Guaratiba 2019, telephone and fax (55-21) 2410-1412, one must make reservations well in advance, since all tours are guided and there are only two daily, at 9:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m., Tuesday through Sunday. Admission is $1.70 a person, and there is no snack bar or restaurant, so be sure to bring provisions. Open daily except Monday from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.

The Casa do Pontal, Estrada do Pontal 3295, telephone (55-21) 2490-3278, because of the energy crisis, is open only Thursday and Friday from noon to 5 p.m., Saturday and Sunday from 10 a.m., admission fee $3.35

Restaurants

Tia Palmira, Rua Caminho de Souza 18, Barra de Guaritiba, (55-21) 2410-8169 serves 10 main dishes, including bobó de camarão, a typical Bahia shrimp stew. Dinner for two without wine, $32.

Quatro Sete Meia, Rua Barros de Alarcão 476, Pedra de Guaratiba, (55-21) 2417-1716. Shrimp moqueca for two is $15. We each had a $2

batida, a cocktail of sugar cane liquor and fruit juice.

LARRY ROHTER

Fuente: NYT